After seeing the dilapidated, crumbling houses of war-torn Syria’s capital, Rania Kataf, began creating a digital archive of the buildings of Old Damascus.

“I was inspired by European photographers who tried to document buildings in their cities during the Second World War so architects could later rebuild part of them,” the 35-year-old said.

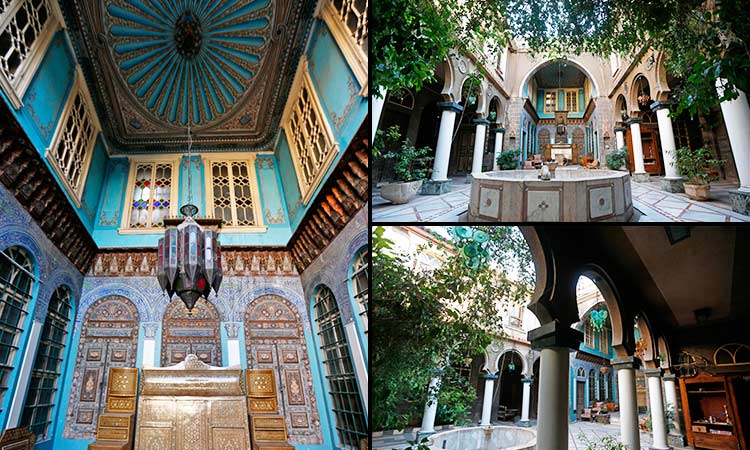

Damascus is famed for its elegant century-old houses, usually two storeys, built around a leafy rectangular courtyard with a carved stone fountain at its centre.

Their many rooms usually include both a summer and a winter guestroom, both looking onto the courtyard.

During the country’s 10-year civil war several of these traditional homes have been abandoned by their owners or damaged in the conflict.

In 2016, Kataf created a group on Facebook called “Humans of Damascus”, to which more than 22,000 Syrians from the capital have sent in photos of their homes.

“You don’t need to be an expert to document something,” she said.

Grand family home

Already her pictures are proving useful in restoration efforts.

Inside a palatial Ottoman-era home called Beit al-Quwatli, Kataf painstakingly captures shots of each section of an ornate wall, then scribbles in her notepad.

The building once belonged to the family of Syria’s first post-independence president, Shukri al-Quwatli.

Part of the home collapsed in 2016 after rebel rocket fire nearby cracked its walls, but today the authorities and private partners are sprucing it up to turn it into a cultural institute.

In 2013, UNESCO decided to add all six of Syria’s World Heritage sites, including the Old Cities of Damascus and Aleppo and the ruins at ancient Palmyra, to its World Heritage in Danger list.

Kataf, who studied nutrition in Lebanon’s capital Beirut, said she was spurred into action after seeing the conflict damage or destroy architectural gems elsewhere in Syria.

“I was scared the same would happen to Old Damascus, so I started to document as many of its details as I could,” she said.

Today some buildings are still at risk of “losing their identity because of money-making projects, or becoming neglected and forgotten after their residents emigrated,” Kataf said.

I live in a museum

But Raed al-Jabri, sitting by the fountain inside his home-turned-restaurant, said he has done all he could to preserve the building’s original beauty.

“We were going to lose the house completely. It was about to collapse and was in desperate need of repair,” the 61-year-old said.

He converted the house into an eatery in the 1990s, investing his profits in the building’s upkeep.

“A Damascus home is not just for its inhabitants,” he said, reminiscing about better days before the war, when tourists flocked to the city.

In another part of the Old City, 50-year-old businessman Sameer Ghadban said he was proud to still live in what was once the home of a famous 19th-century Algerian who had resisted the French occupation of his homeland, then sought refuge in Syria until his death.